Yesterday, while actively following the events in Ferguson, I was asked the following by @GenXMedia:

White Suburban America seems riddled with apathy, excuses and disconnect about #Ferguson. Any ideas why?

Upon further prompting, it became clear that @GenXMedia wanted a response to each of the three things that White Suburban America is riddled with: apathy, excuses, and disconnect.

It is important to note that, as many of you know, this important topic does not fall squarely in my “wheelhouse.” I mostly think about institutions and strategic models of politics. That said, and with the usual warning that you get what you pay for, here’s my promised response.

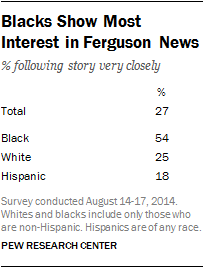

Apathy. If we define apathy as anything less than intense interest in the unfolding story in Ferguson then yes, unsurprisingly, it is clear that more white voters are apathetic toward the events in Ferguson, with 54% of black respondents saying they are following the story very closely, while only 25% of white respondents say the same thing:

(Here is the full Pew survey and write-up.) It’s beyond my scope here but, to understand the intricate question of how race, civil rights, and Ferguson interact, it is important to note that only 18% of Hispanic respondents said they are following the story very closely.

Sadly, these numbers aren’t surprising to me. Apathy is a “choice” only in the technical sense. From a common sense standpoint, apathy is the absence of a choice to care/pay attention and “not choosing to pay attention” is a heck of a lot easier when the events seem less proximate to yourself.

I’m not saying that it’s rational to be apathetic, particularly about something as important and extreme as the events in Ferguson, but the results today are consistent with several decades of research into political attitudes in America, including the fact that the perception of “linked fate” is far more prevalent among black Americans than either whites or Latinos.[1] Linked fate is a key concept in the study of race and politics. A recent review of this literature describes linked fate as follows:

Linked fate is generally operationalized by an index formed by the combination of two questions. First, respondents are asked: “Do you think what happens generally to Black people in this country will have something to do with what happens in your life?” If there is an affirmative response, the respondent is then asked to evaluate the degree of connectedness: “Will it affect you a lot, some, or not very much?” [2]

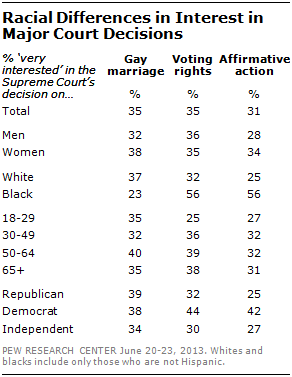

Moving beyond (and/or in addition to) linked fate, one can also argue that the incentives (or perhaps proximities) of black and white Americans differ with respect to law enforcement. Setting aside a more detailed discussion of this, just note the similarity between the racial breakdown of people closely following the events in Ferguson with the analogous breakdown of interest across gay rights, voting rights, and affirmative action in 2013:

Excuses. It’s well established that white Americans generally perceive racism to be less prevalent and less important than black Americans. Discussing racial attitudes in the post-Civil Rights era, Brown, et al. write

In the new conventional wisdom about race, white racism is regarded as a remnant from the past because most whites no longer express bigoted attitudes or racial hatred.[3]

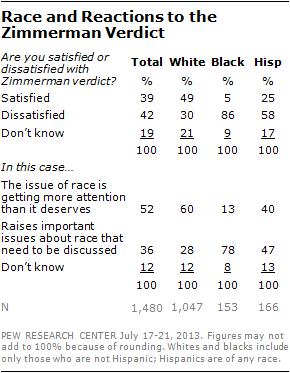

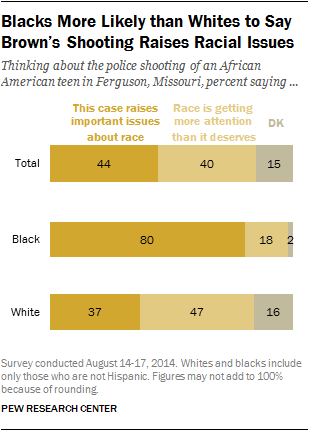

Simply put, the Pew survey does nothing to contradict this conclusion. Specifically, 47% of white respondents said that “race is getting more attention than it deserves” in the coverage of the shooting of Michael Brown, while only 18% of black respondents, and only 25% of Hispanic respondents, agreed with that statement (see here for the full breakdown):

In the end, it’s important to note that the racial divide in attention being paid to Ferguson is in line with the racial differences in individuals’ beliefs that race is an important part of the narrative. While it is impossible to gauge causality here—namely, are fewer white people paying attention to Ferguson because they think it’s not about race or are more white people saying Michael Brown’s shooting wasn’t about race because they’re not paying attention to Ferguson—both are consistent with avoidance: simply put, issues like homelessness, inequality, and discrimination are difficult to get many people to pay sustained attention to. I’ve argued elsewhere that politics is about problem-solving, and people like to debate problems they think can be solved. Race is arguably the most complicated problem to solve. While by no means admirable, avoidance of the issue by those who can (i.e., white people) is not surprising.[4]

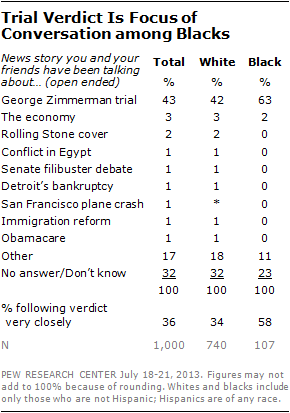

Disconnect. I’m not exactly sure how “disconnect” is different from both apathy and excuses, but I’ll take a stab and interpret this as “why do white people not seem to connect the events in Ferguson with race?” My response here, sadly, is that they kind of do—at least insofar as the attitudes here are consistent with other similar racially charged events. For example, following the acquittal of George Zimmerman in July 2013, Pew conducted a poll gauging reactions and attention to the case. The racial breakdowns of responses to each are very similar to those just found in the case of Ferguson, with 60% of whites thinking the issue of race was getting more attention than it deserves, and only 13% of blacks feeling that way:

Similarly, 63% of black respondents mentioned talking about the trial with friends, versus only 42% of white respondents:

Similarly, 63% of black respondents mentioned talking about the trial with friends, versus only 42% of white respondents:

Conclusion. My own view on this is that Ferguson is most decidedly a racial issue. This isn’t the same as saying that anyone involved is (or isn’t) racist. Indeed, that issue, to me, misses the larger and more important point. In fact, while the racial realities of Michael Brown’s death—an unarmed black American killed by a white police officer—undoubtedly thrust race forward into the discussion, race should have been part of the discussion anyway.

That’s because any of the multiple dimensions of the context of Ferguson—the historical discrimination, the economic inequality, the political disparities, the unrepresentative political institutions, and the more general “special” features of local elections, to name just a few—make the issue of not only Michael Brown’s death, but also the largely and sadly ham-handed response a racial issue.

So, why don’t more white people see this? A succinct (though definitely not exculpatory) answer is inertia: attitudes, like objects, tend to stay the same until acted upon an outside force. The reality of America is that white Americans are less likely to see their fates as being linked with those of black Americans and (perhaps because) they are less likely to face the everyday inequalities faced by far too many black Americans. In other words, and quite literally, most white Americans don’t often encounter an outside force with respect to race—definitely not like many black Americans do. Whether they achieve this through apathy, excuses, and/or disconnect is a trickier question, but the correlation—the reality that race still divides Americans’ perceptions of politics and power—is sadly indisputable and robust, even in the 21st century.

____________

[1] See Dawson, Michael C. Behind the mule: Race and class in African-American politics. Princeton University Press, 1994.

[2] From Paula D. McClain, Jessica D. Johnson Carew, Eugene Walton, Jr., and Candis S. Watts. 2009. “Group Membership, Group Identity, and Group Consciousness: Measures of Racial Identity in American Politics?” Annual Review of Political Science (2009), p. 477.

[3] From Michael K. Brown, Martin Carnoy, Troy Duster, and David B. Oppenheimer. Whitewashing race: The myth of a color-blind society. University of California Press, 2003, p.36.

[4] Another, stronger, view of this is called “white privilege,” which describes the fact that issues that can be avoided are also deemed less important to others, without noticing that the ability to avoid these issues is not independent of race. (Thanks to Jessica Trounstine for adroitly directing me to this connection, as well as posting this telling graphic.)

I appreciate your thoughts here. Very insightful. Excellent post.

Thanks, Jonny. Always nice to get the shout-out—just too bad that it takes events like #Ferguson to prompt it.